My review of this “haunting, lyrical, and unsparing coming-of-age novel” appeared in the August issue of The Nervous Breakdown.

Here is the link:

The Nervous Breakdown

Author Website

My review of this “haunting, lyrical, and unsparing coming-of-age novel” appeared in the August issue of The Nervous Breakdown.

Here is the link:

The Nervous Breakdown

“Are we middle class?” my eight-year-old daughter Ella asked me.

“Yes. Why?”

“At camp, when I told one of my cabin mates we don’t have cable TV, she said we must be really poor.”

“What did you say?” I asked.

“That we just don’t think it’s worth the money, but she didn’t believe me. She wanted to know if we don’t have a phone or refrigerator, either.”

Later that day, Ella watched me pull the New Yorker out of the mailbox. The cover showed a ship like the Titanic sinking while men in tuxedos smoke cigars and drink champagne in a lifeboat, laughing at the demise of the suckers left behind.

“What’s that mean?” she asked.

I explained how we’re “all in the same boat,” the middle class and poor people, as the rich escape the recession unscathed, even better off. “The gap between the very rich and everybody else has never been greater than before the Great Depression,” I said, quoting my economist husband.

I showed Ella the book her dad was reading, Winner-Take-All-Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer—And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. Since we don’t have the distraction of cable TV, I should be able to find time to read this book and give Ella numerous examples of how that New Yorker cover is a picture of twenty-first century America.

But all you have to do is read the newspaper—with stories daily about how companies selling $250,000 playhouses and renting private jets for summer camp visits are booming—to see that the very rich are weathering the shipwreck of the recession.

“Why doesn’t somebody do something?” Ella asked.

It’s hard to explain to a child why income inequality is allowed to grow unchecked. But I tried: “Because it’s in the best interests of the very richest people, and they have enough money to buy political influence.”

From her face, I could tell it wasn’t what she wanted to hear. Ella is a patriotic girl, wrapped up in a halter dress that looks like a flag. I thought she wanted her country, like her parents, to remain infallible, at least for a few more years.

But maybe I was putting too many of my thoughts in her head. “What I meant,” she said. “is why can’t we get cable TV?”

With the kids still at camp (we pick up Ella the day after tomorrow), James and I made our getaway. In forty-five minutes, we landed at Ann Hatheway’s Cottage, a quaint and quirky bed and breakfast built as a replica of the childhood home of Shakespeare’s wife, thatched roof and all. Staunton, Virginia has sweeping views of the Blue Ridge Mountains, proximity to first-rate hiking, a downtown full of chic independent cafes and bookstores, the Woodrow Wilson Library, and Mary Baldwin College. But the main tourist attraction for us is Blackfriars Playhouse, a small variation on The Globe in London.

We saw The Tempest. As I described it to Ella, in the e-mail I sent her at camp, it is about a magician, like Harry Potter. As James explained to me, it’s a metaphor for the destructiveness of colonialism. As the director said in the program, it is Shakespeare’s good-bye to his audience, as he retires from writing and casting plays the way Prospero retires from writing and casting spells. As I felt, on a visceral level, The Tempest is about the evils of slavery.

Twelve years before the start of the action, Prospero’s brother stole his title, became Duke of Milan, and put Prospero and his three-year-old daughter Miranda on a leaky boat in wild seas to die. Miraculously, they shipwrecked alive on an island inhabited by one man—Caliban—a bastard whose mother was a witch. At the start of the play, Prospero uses his magic to enslave the flesh-and-blood Caliban and the invisible sprite Ariel.

Caliban remembers how Prospero tricked him with kindness, then used his trust to enslave him: “When thou cam’st first,/Thou strok’st me and made much of me. . . and then I loved thee/And showed thee all the qualities o’ th’ isle. . .” Caliban, who had been master of the whole island, was now not even master of himself: “Cursed be I that did so! . . . For I am all the subjects that you have,/Which first was mine own king.”

Prospero responds: “Thou most lying slave,/Whom stripes may move, not kindness! I have used thee/(Filth as thou art) with humane care.” Miranda taught Caliban her language and European manners, at first treating him like a peer and then like a dog.

When Caliban schemes to kill his master in his sleep, I rooted for the death plot to succeed. Shakespeare could not have foreseen such a reaction four hundred years ago. Nor could he have imagined the production I saw, with women playing men and the three goddesses whom Prospero conjures to bless his daughter’s betrothal played by men dressed as drag queens, belting out Motown rhythms. Shakespeare certainly could not have known that I would be watching his play next to The Stonewall Jackson Hotel, in an area in the South where street names and monuments won’t let us forget, as we walk past them every day, the horror of slavery in our country’s past.

Both my children are at sleepaway camp. For the first time since I became a parent seventeen years ago, my husband and I are a childless couple. (And this is how I spend our opportunity for a second honeymoon, you ask—writing a blog post?)

Since my son’s first experience, at age eleven, sleepaway camp has been the highlight of his year, and I hope the transformative power of a super-long sleepover party will work its wonders on my eight-year-old daughter, too.

As we drove away from my daughter’s camp, the head counselor said, in her charming Australian accent, “No news is good news.” We have not heard a quack, so everything must be ducky.

I didn’t worry when my son hadn’t contacted me (he is seventeen, after all), even after I e-mailed and texted him asking for confirmation that all was well. When he did call, I knew something was wrong.

“One of my campers had to go to the emergency room in the middle of the night,” he told me. “Asthama attack. A really bad one.” With the senior counselor at the hospital all day helping the boy with the medical crisis, my son had to take care of the remaining seven campers in his cabin by himself. He didn’t get his usual hour off in the morning, but he got someone to cover for him right before dinner, so he could make a quick call. I was touched to be the one he reached out to.

I didn’t get a call the next day, which was a good sign. But the day after I did. “The boy went back to the emergency room,” my son said. “I’m by myself again.” He sounded tired. “Don’t get me wrong,” he said, after complaining about his sleep being interrupted again by an ambulance. “Everything is great here. I’m not sorry I came. I’m just venting to you because I can. I have to be strong in front of my kids.”

His kids. The phrase sounded funny. After all, he is my kid. “It’s super fun here when the kids do what I ask them to,” he said, “and frustrating when they don’t.” He didn’t say, “now I understand what you go through as a parent,” but I could hear it in his voice.

We were going to the beach. So we needed some beach reads.

Not for me, but for my eight-year-old daughter. And not for lounging at the beach, but for driving to the beach. Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts is a long way from Charlottesville, Virginia, especially with a stop in New York City along the way.

The afternoon before departure, we went to the Charlottesville Central Library and found one of the most important people in this town: the children’s librarian. When she suggested familiar books, Ella said, “Don’t you remember? I read that last year,” as if anybody could keep a running list in her head. (I certainly can’t.) Finally, we descended the grand stone stairs with four books (Matilda Bone by Karen Cushman, Night Journey by Avi, A Drowned Maiden’s Hair by Laura Amy Schlitz, and A Girl Named Disaster by Nancy Farmer). Though Ella doesn’t get motion sickness, we also borrowed an audio book (Peter Pan) just in case.

The traffic was horrific. After the seven hours to New York City, what should have been a forty-minute trip from Manhattan to Newark to pick up my in-laws at the airport took hours and involved standing still for more than forty minutes at a time. I found Ella a bathroom downtown, and when we returned, the car hadn’t moved. We worried about running out of gas. But what kept us from screaming at each other and at the unhelpful police officers was our little girl in the back seat, making not a peep about being bored. After all, she had books to read, whose titles, with words like “journey” and “disaster,” seemed wildly appropriate to the situation.

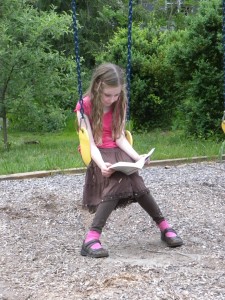

Once we arrived in Martha’s Vineyard, for the family reunion, it was Cousin Time: decorating attic bedrooms with “no grown-ups allowed” signs, collecting dismembered crab carcasses to decorate sand castles, playing hide and seek until dark then poker until the eyes drooped. Halfway through the trip, we visited a charming used books store and bought Ella a pile of paperbacks for the ride home: Mildred Taylor’s The Road to Memphis, Lynne Reid Banks’s The Farthest Away Mountain, Gary Paulsen’s Woodsong, Scott O’Dell’s Streams to the River to the Sea, Avi’s Poppy, and Avi’s Poppy and Rye. When Ella started to read them in the five-minute drive back to the rental house, I had to hide the stash so she would have something fresh to read through the traffic jams we would encounter on our return to Virginia. But she managed to find a cousin’s book (Rick Riordan’s The Red Pyramid), and I wish I had taken a picture of her with two of her eight cousins sprawled on our bed, reading it together.

But I do have these three pictures of reading, two on vacation, and one at home. Every time I look at them, they make me want to pick up a book.