People always talk to me on the plane, except last night. I sat in the middle and ate the roast beef sandwich I’d stuffed into my messenger bag. Then I leaned back, closed my eyes, and imagined no one could see me. Finally, soundless and still, I let the tears fall.

I don’t usually cry in public. It’s one of our last taboos. You can appear to strangers in your underwear, but letting them see you cry feels dangerously intimate. So the two women on either side of me didn’t ask where I was going or where I’d been, as my seatmates usually do. The twenty-something on my left kept typing up revised guidelines for new hires, and the sixty-something on my right paged through her paperback.

I cry every time I drop my son off at college. Normally I hold everything together until no one can see me. This time I was too rushed to dash into the public restroom and lock myself in a stall, where I could let my face redden, then powder the blotches away.

On this trip, I was helping my son move into a new college as a transfer student, far from home. I was leaving him the car, and I hoped he would drive safely. I hoped he would make good friends this time and be happy. I hoped he would be better at keeping in touch with me than I had been with my own mother. I didn’t want to burden him with my hopes and worries. But maybe I was wrong.

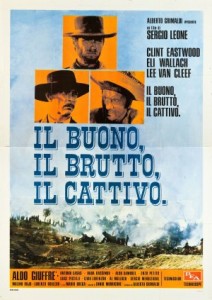

A few months ago, my son and I watched a DVD of the clever, quirky romantic comedy “Enough Said.” Julie Louis Dreyfeus plays a single mom whose daughter is about to move away to college. Through the whole movie, the mom complains about how her life will end once her baby abandons her. It will be the worst day of her life. She might have to lock her daughter’s room and never let her go.

At the end of the movie, my son paced and grimaced. “You didn’t like it?” I asked.

“I did,” he said. “It’s just. . .”

“Just what?”

“It’s just . . . how come you weren’t upset when I left for college?”

“I was.”

“You didn’t cry.”

“I did,” I said. “In the bathroom. In the car once I dropped you off. But I wanted you to think I was strong. I didn’t want you to see me fall apart.”

“Why?”

Good question. Maybe next time I won’t wait till I get on the plane. I’ll tell him how I feel as he weaves through 70-miles-an-hour traffic on the way to the airport. I’ll think of this passage from John Updike’s story, “My Father’s Tears,” and try to be more eloquent:

“Come to think of it, I saw my father cry only once. It was at the Alton train station, back when the trains still ran. I was on my way to Philadelphia to catch the train that would return me to Boston and college. I was eager to go, for already my home and my parents had become somewhat unreal to me, and college, with its courses and the hopes for my future they inspired and the girlfriend I had acquired in my sophomore year, had become more real every semester; it shocked me—threw me off track, as it were—to see that my father’s eyes, as he shook my hand goodbye, glittered with tears.

“I blamed it on our shaking hands: for eighteen years, we had never had occasion for this ritual, this manly contact, and we had groped our way into it only in the past few years. He was taller than I, though I was not short, and I realized, his hand warm in mine while he tried to smile, that he had a different perspective than I. I was going somewhere, and he was seeing me go. I was growing in my own sense of myself, and to him I was getting smaller. He had loved me, it came to me as never before. It was something that had not needed to be said before, and now his tears were saying it.”