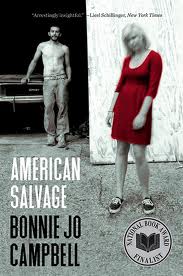

American Salvage by Bonnie Jo Campbell. New York: Norton, 2009. Review by Sharon Harrigan

“Beware ye who enter here, and yet you should and must” begins a blurb for American Salvage published in Small Press Review. Entering into Campbell’s fictional world of self-destructive, meth-addicted, racist, misogynist, child-raping, self-immolating, economically depressed and emotionally and geographically trapped characters is not a stroll in the park. But if we, as readers, want to become informed and transformed, we have to be willing to travel into dangerous territory. And as writers, we need to be willing to go deep into the darkness and secrets of the world we live in, which Campbell does fearlessly.

The first story, “The Trespasser,” is so raw and horrifying that I was riveted but also a little afraid to read on right away, needing to pause and absorb its grief. The story is told through the eyes of “the daughter,” a thirteen-year-old girl from a functional middle class family who discovers that her summer house has been trespassed. The daughter’s life will never be the same, after she has seen the mattress the trespasser threw outside as soon as the men she allowed to gang rape her for drugs are gone, the mattress “crusted with jism.”

We also get the point of view of the sixteen-year-old girl who is only known as “the trespasser.” The contrast between the danger and hopelessness of the trespasser’s life and the surface tranquility of the daughter’s life creates a tension that would be absent with only the daughter’s perspective.

Campbell cleverly hands us the daughter’s story by letting us read over the shoulder of the trespasser, who is also trespassing the daughter’s diary. It is through the absence of horror in the daughter’s life that we infer the presence of that horror in the trespasser’s experience. “The daughter has made it more than thirteen years without having spent a night with her dresser pushed up against her bedroom door to keep her mother’s friends out. Nobody has ever burned her face with a cigarette.”

The list gets worse, and this story is so vividly written that I could feel the pain of the trespasser in my stomach. My pain was rewarded with Campbell’s compassion and her gift for opening a window into a world that is not often enough portrayed in fiction. After all, who really wants to read more stories about privileged white middle class people and their petty problems?

The second story, “Yard Man,” is longer (27 pages instead of 4) and told at a much more leisurely pace. It is still filled with sadness and hopelessness, but is not as heartbreaking as “Trespassers.” The theme is the death of a marriage. Jerry is the titular “yard man,” trying desperately to salvage his marriage to Natalie (all the characters in this book are trying to salvage something—a wonderful reflection on the title), a beauty and his high school sweetheart who married and had children with someone else, then divorced and married him.

His efforts are futile because Natalie comes from a more well off family (she grew up in a real house and constantly complains about having to live in a ramshackle cottage on the grounds of a metal salvage plant). We have a sense of foreboding when a snake appears. Natalie shrieks and wants Jerry to kill it, but he can’t; he thinks it is too beautiful. Nor can he kill the bees and other critters that invade their house. The wild is taking over the civilization they can’t impose on their lives. We know they are doomed when, two-thirds of the way through the story, we are told: “If only they could all remain together forever like this, he being the yard man, with his wife and the kids. . . and the snakes and bees and deer and ground birds and nighthawks . . . out of his wife’s line of sight. . . That was one way it could have gone.”

“Solutions to Brian’s Problem” is, like “Trespassers,” short and wrenching, leaving the feeling that the world is hell. But the structure–a list of possible ways Brian can fix the problem that his wife is a meth addict and can’t take care of their children, with each possibility more impossible than the next–is inherently humorous, which I found helped the medicine go down.

“The Inventor” and “Fuel for the New Millennium” confront timely and terrifying themes. They are about technology failing, paranoia, and our general overreliance on and misunderstanding of technology.

In “The Burn” the violence of the story is physical and painful. The protagonist, Jim, has almost nothing at the beginning of the story, and progressively manages to have less and less. He runs out of gas two blocks from his house and has only enough money to buy two gallons. His envy for the guy who pulls into the gas station parking lot in a new Ford truck is palpable. He says the guy “must have a union job that pays twice what Jim makes at the foundry.” He accidentally burns himself and insists on checking out of the hospital prematurely. Then he alienates the lesbians who live above him and the black Jehovah’s Witnesses who knock on his door. Because of his prejudices, he dismisses the only people who might help him survive.

I applaud Campbell for embracing dark themes—drug addiction, incestuous rape, death by drowning, car accidents, and being trapped by economic circumstances with no way out, the economy as enemy. This book inspires me to try to emulate Campbell’s empathy. The way she completely inhabits these lost souls, gives them a voice, and shows both their humanity and hope is big hearted and humbling.